As Valentine’s Day approaches, millions of Australians will be encouraged to swipe, match and message online in the search for romance. Dating apps and social platforms typically see a surge in activity during this period, driven by the promise of companionship, intimacy and connection. But alongside genuine relationships, this heightened activity also creates fertile ground for romance scams, where emotional vulnerability is deliberately exploited using increasingly sophisticated digital techniques.

Romance scams in Australia increasingly combine emotional manipulation, investment fraud and emerging technologies. Understanding how these scams unfold helps explain why warning signs are often missed.

Romance scams are a form of fraud in which a scammer pretends to form a genuine romantic relationship in order to exploit trust for financial gain. They most often begin on dating apps, social media platforms, or messaging services and typically develop over time rather than through immediate requests for money.

Scammers usually create convincing fake profiles and invest significant time in building an emotional connection before introducing financial requests. This process, often referred to as love-bombing, involves frequent messaging, expressions of affection and discussions about future plans designed to establish trust and emotional dependence.

As trust builds, the scam shifts. Victims may be asked to help with an emergency, send money temporarily, or participate in what appears to be a legitimate financial opportunity. These requests are structured to discourage outside scrutiny and normalise secrecy, making the scam difficult to recognise while it is unfolding.

Romance scams are also referred to as dating scams or romance fraud. In recent years, Australian authorities have increasingly used the term pig-butchering to describe long-term romance scams that transition into investment fraud, particularly involving cryptocurrency or offshore trading platforms. In these cases, losses are escalated over time and recovery is unlikely.

Current romance scam trends in Australia

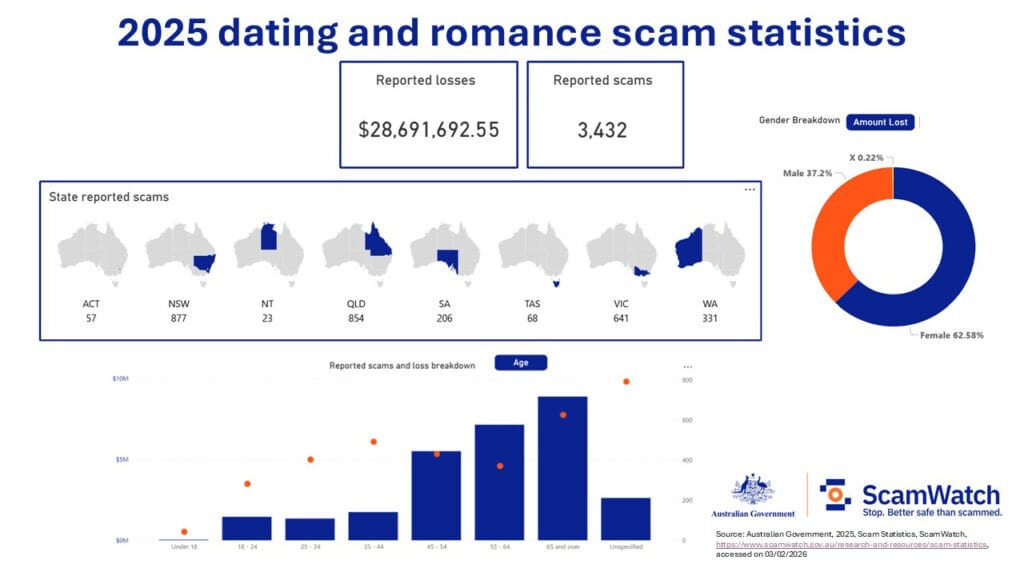

In 2025, Australians reported 3432 dating and romance scams, with total losses of about $28.7 million (AUD), and an average loss per victim of about $8360. Losses are concentrated among older Australians, particularly those aged 55–64 and 65 and over. Women account for nearly two-thirds (about 63 per cent) of the total financial losses.

State-level reporting shows New South Wales (877 reports) and Queensland (854 reports) recorded the highest number of cases, followed by Victoria (641) and Western Australia (331). Smaller jurisdictions such as the Northern Territory (23) and the ACT (57) report far fewer cases, largely reflecting population size rather than lower risk.

2025 ScamWatch dating and romance scam statistics (Author supplied image)

2025 ScamWatch dating and romance scam statistics (Author supplied image)

One evolving pattern is the integration of emotional trust with financial deception. Scammers may encourage victims not only to send money, but also to invest jointly in what appears to be profitable opportunities, such as cryptocurrency trading or offshore ventures. The Australian Federal Police warned Australians about organised fraud syndicates that lure people through dating apps before encouraging investment transfers to scam accounts.

Another emerging trend is the use of AI-assisted impersonation, including deepfakes. Europol has documented how deepfakes can support fraud and social engineering. The Europol Innovation Lab warns that advances in AI now make it technically possible to manipulate audio and video content in near real time, including in videoconferencing environments. As a result, voice messages, images and even live video interactions can no longer be assumed to provide definitive proof of identity.

Key red flags people often miss

Many red flags are difficult to identify while a relationship is unfolding because manipulation begins with emotional engagement rather than obvious requests for money.

One common feature is unusually rapid emotional intimacy. Expressions of affection and commitment appear early, creating trust before meaningful verification occurs.

Another frequently missed signal is repeated avoidance of video calls and in-person meetings. Scammers typically provide plausible explanations, such as travel, busy schedules or technical issues, as part of a broader social engineering strategy used to avoid identity exposure. Individually, these explanations may not raise alarm. It is their persistence that matters.

These scams deliberately avoid face-to-face verification, relying instead on sustained text-based communication to build emotional attachment before any financial request is made.

Financial escalation is often gradual. Requests for help or suggestions to invest together tend to be framed as temporary, shared, or confidential rather than urgent or exploitative. Secrecy is often positioned as trust or loyalty, discouraging individuals from discussing the relationship with others.

Once the relationship feels established, requests for financial help and personal financial information are gradually introduced. Concerningly, scammers may suggest “investment opportunities,” often framed with assurances of shared benefit, which can normalise financial risk and delay scepticism.

A further trend is the rapid movement of conversations away from dating apps and mainstream social media. Once communication shifts to private messaging services such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal or WeChat, platform-level safeguards weaken. This reduces opportunities for moderation and reporting and limits the chance that friends, family, or moderators might notice inconsistencies or raise concerns.

A simple checklist to protect yourself and report early

Practical actions can reduce harms from romance scams and support early intervention:

- Do not send money, gift cards, cryptocurrency or financial details to someone you have not met in person.

- Be cautious if a relationship becomes emotionally intense very quickly or if video contact is consistently avoided.

- Treat any move towards financial help or shared investment with caution, particularly before meeting face to face.

- Keep records of messages, profiles and requests rather than deleting conversations immediately.

- Report suspicious behaviour within the app or platform before blocking the account.

- If money or personal information has been shared, report it early to the Australian Government’s ScamWatch and cybersecurity website.

Early reporting is not an admission of error. It is a preventative cybersecurity action that supports national scam intelligence and helps protect others.

Romance scams persist in Australia not because people are careless, but because emotional trust is exploited. As online platforms increasingly mediate personal relationships and AI tools lower the cost of impersonation, cybersecurity must be understood as a shared responsibility that includes protecting the social spaces where trust is formed.