All roads lead to PQC

Every few months, another “quantum-safe” technology is marketed as the real answer, usually with the claim that post-quantum cryptography isn’t enough. PQC is too new, too slow, too fragile, too unproven. One person I spoke to even described adopting PQC as “shuffling the furniture on a sinking ship,” as if the standards effort itself is the problem.

These lines get attention, but they don’t hold up once you look at how actual systems work. The alternatives being promoted, such as QKD, information-theoretic schemes (for brevity, “ITS” here means non-QKD physical or theoretical methods), and specialised hardware, focus on securing a link or a tightly controlled environment. What they ignore is everything else a real system must do: authenticate devices, validate certificates, sign updates, interoperate across clouds, and function at internet scale.

And once you account for those requirements, the irony becomes obvious: these same alternatives still end up relying on PQC. They may guarantee secrecy inside a narrow channel, but as soon as they interact with the wider digital ecosystem, PQC becomes unavoidable.

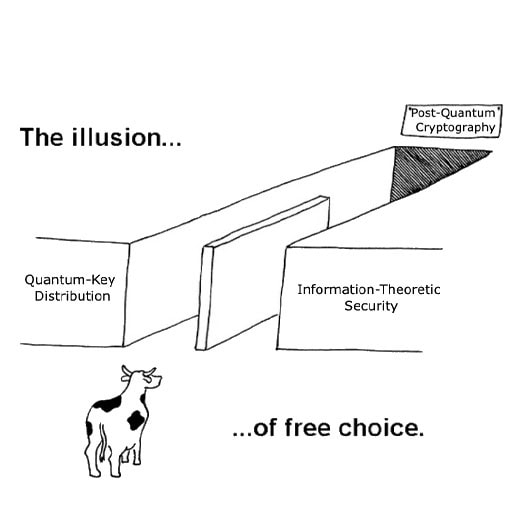

That’s the point behind the picture: it feels like a menu of choices, but nearly all paths converge back onto the same foundation because the architecture of modern infrastructure leaves very little room for anything else.

This isn’t dismissing QKD, ITS, or hardware-rooted approaches. It’s correcting the narrative that PQC is optional. In practice, it isn’t.

Why So Many Vendors Claim PQC Is “Not Enough”

The incentives are obvious: bold critiques attract attention and help differentiate emerging technologies. So you hear familiar lines about how PQC is too new, too theoretical, too slow, too fragile.

The reality is simpler: these alternatives each solve one slice of the problem. A channel. A fibre. A physical boundary. None of them solve the full lifecycle of identity, updates, trust distribution, certificates, cloud interaction, and interoperability. And once you trace an actual deployment, the irony shows up quickly: the same vendors insisting PQC is insufficient still need PQC somewhere in their architecture.

A few examples:

QKD still needs authentication.

The optical channel provides secrecy, not identity. Devices (especially classical) still need authenticated channels, signed updates, and certificate validation, all software trust functions requiring – you guessed it – PQC.

Information-theoretic systems still need secure key establishment.

A one-time pad is perfect after the pad exists. Moving, refreshing, and coordinating that key material at scale requires a secure classical channel with PQC-grade signatures.

Hardware-rooted trust still depends on software trust.

Secure enclaves and TRNGs can generate entropy, but firmware, attestation, distribution, and lifecycle management all rely on classical or PQC signatures.

The claim that “PQC isn’t enough” isn’t usually a technical argument; it’s a contextual mismatch between what these technologies do and what modern infrastructure requires.

The Non-Negotiable Reality of Digital Infrastructure

Strip away the marketing, and the technical picture is straightforward: modern systems run on software-based trust – identities, signatures, certificates, updates, and secure communication across devices that don’t trust each other by default. That layer isn’t optional; it’s what keeps the internet, cloud services, mobile ecosystems, and enterprise networks usable.

This is where every “alternative” eventually hits a wall. QKD might secure a fibre link. ITS might protect a controlled environment. Hardware enclaves might strengthen endpoints. But the moment these systems need to authenticate devices, sign firmware, validate certificates, or interact with browsers, mobile apps, cloud APIs, or external partners, they return to the domain of software trust.

No physical or link-level technology replaces that. They solve narrow, sometimes critical problems, but not the global architecture everything else depends on.

PQC does. It runs on commodity hardware, integrates with existing protocols, deploys through software, and scales across the messy, heterogeneous systems the world already uses.

This isn’t about which technology is theoretically strongest. It’s about which one fits the architecture we already have. And right now, only PQC does.

The Illusion of Choice: Confusion as a Side Effect

Marketing often frames “quantum-safe” technologies as mutually exclusive paths. In practice, this framing creates confusion, not clarity.

When vendors claim PQC is inadequate or that some alternative will make today’s standards obsolete, organisations hesitate. Teams postpone migrations, debate non-problems, or compare technologies that were never competing. The result is predictable: paralysis by analysis at exactly the time when forward progress matters most.

And again, the irony is that these alternative technologies still rely on PQC somewhere in their lifecycle. They secure a link or a controlled environment, but everything that interacts with the broader internet, like identity, updates, certificates, and cross-organisation trust, still requires PQC.

Once you map an organisation’s actual requirements, the illusion of choice disappears. Alternatives add value, but they don’t replace what PQC provides.

In workshops and roundtables that we hosted, more than once I have encountered the question: QKD or PQC? My answer is this: PQC for today, QKD for tomorrow.

Where Alternatives Fit (and Where They Don’t)

Technologies like QKD, ITS, and specialised hardware all have legitimate roles. QKD is excellent for point-to-point secrecy on controlled fibre. ITS offers strong guarantees once key material exists. Hardware modules reinforce local trust boundaries.

But their strengths don’t extend to what modern systems need at scale. QKD doesn’t authenticate devices or sign updates, nor can it communicate with classical devices. ITS can’t practically distribute key material across global infrastructure. Hardware modules don’t replace distributed trust.

If anything, these approaches reinforce why PQC is essential. They perform best when layered on top of a robust cryptographic foundation, not when marketed as its replacement.

The Scalability and Timeline Problem

Even if alternatives worked flawlessly, the limiting factor isn’t theory – it’s deployment. The world needs a solution that can protect billions of classical devices, across untrusted networks, on ordinary hardware, within a realistic timeline.

That immediately rules out most alternatives. QKD will not be rolled out across the public internet in any meaningful timeframe. ITS won’t distribute key material at global scale. Hardware-bounded approaches won’t replace software trust across organisations.

PQC, on the other hand, scalably fits into existing protocols and infrastructure. Organisations can deploy it with software changes rather than new physical installations. It aligns with the size of the problem and the time available.

The real question isn’t which option is theoretically strongest. It’s which one can be deployed everywhere before quantum attackers arrive. And on that metric, PQC is the only realistic foundation.

PQC Is the Foundation We Build On (For Now)

The quantum-safe discussion is often framed as a contest between competing technologies. It isn’t. Modern systems need a trust layer that works everywhere, including across browsers, mobile devices, cloud platforms, certificates, update mechanisms, partner integrations, and untrusted infrastructure. Only PQC fits that requirement today so neatly.

Alternatives are valuable, but they sit on top of the stack, not underneath it. The more their marketing suggests otherwise, the more organisations hesitate, delaying the only upgrade that can actually be deployed at internet scale, within the necessary timelines.

The point isn’t that PQC is perfect or that other approaches won’t mature. It’s that right now, PQC is the only technology capable of securing the trust functions the world already depends on. Everything else, like QKD, ITS, hardware-rooted channels, can complement it, but not replace it.

Like it or not, PQC is the key for now. The sooner we accept that, the sooner we can get on with the part that matters: implementing it.